1.2 “Romance de la pérdida de Alhama” – Anónimo

5 min read•february 12, 2023

Kashvi Panjolia

Kashvi Panjolia

AP Spanish Literature 💃🏽

24 resourcesSee Units

The "Romance de la pérdida Alhama" is a poem of the form known as a romance. Given that most of the legends in the Iberian Peninsula were transmitted orally, there is no doubt that the fusion of music and poetry gave rise to a rich tradition of "romances" in medieval literature, including this notable work.

The romance of the Middle Ages as a literary work has several characteristics:

- It is octosyllabic, meaning that each verse has 8️⃣ syllables

- Romances have assonant rhyme 🅰️🅰️ on even verses

- Often, they include a chorus 🎶, or a repeated verse that harkens back to the central idea

- They have an unlimited ♾️number of verses

The poem is set in the last stage of Al-Ándalus, around the year 1490. The titular Moorish king was Boabdil, a weak king who ruled the south of the peninsula from the city of Granada. Granada was the last Moorish kingdom remaining during the Spanish Reconquista, so the fall of Granada signified the end of the era of Convivencia and the time of the Moors in Spain. Each stanza highlights the inevitability of the Catholic kings conquering Alhama and the rest of Al-Andalus.

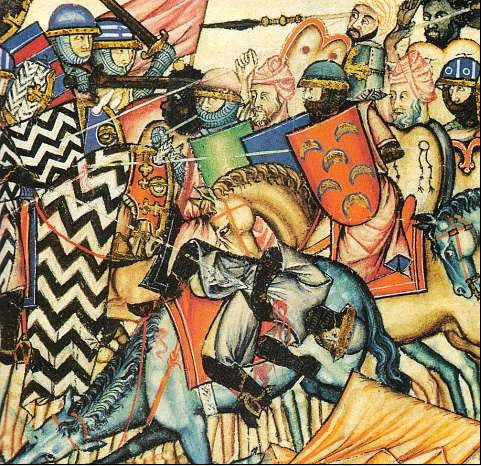

Battle of the Reconquista, from the margins of the Cántiga de Santa María. Image courtesy of Wikimedia.

Summary

The poetic voice begins the romance in medias res (in the middle of the action). It features the Moorish king walking through his city when he receives news that Alhama, a strategic hill in Al-Andalus, has been conquered by Christians. The king is unable to cope with the news and burns the letters in the fire and kills the messenger (“las cartas echó en el fuego / y al mensajero matara"). Meanwhile, the chorus — "¡Ay de mi Alhama!" — represents the voices of the despairing Muslims faced with the news.

In stanzas 3 and 4, the king seeks to mount a resistance. When he gets off a mule and gets on a horse, ("descabalga de una mula / y en un caballo cabalga") he seeks to make himself look more powerful and more like the leader he thinks he is. He orders the trumpets to sound to encourage his soldiers' desire to fight. Later, the poetic voice presents the resistance as futile despite forming a great squadron (“uno a uno y dos a dos / juntado se ha gran batalla”). Meanwhile, the chorus continues to remind the audience of the impact of the loss of Alhama. 😭

In the climax of the romance, as the king tries to foster the spirit of fighting among his soldiers, he is confronted by an elderly Moor who announces to all the Moors that the fierce Christians had already taken Granada, (“cristianos de braveza / ya nos han ganado Alhama”), a fact the army didn't know yet. In addition, an alfaquí — a cultured and wise man in the Arab communities of Al-Ándalus — scolds the Moorish king for having killed the Bencerrajes (a noble family with whom the royal family competed), as well as having accepted converts to Christianity in the court. Lastly, the alfaquí declares that the king deserves to lose his kingdom and that the Moors deserve to lose Granada and Al-Andalus forever.

"La salida de la familia de Boabdil de la Alhambra"—The Departure of Boabdil's Family from the Alhambra, Manuel Gómez-Moreno González (1834-1918). Image courtesy of Wikimedia.

Analysis

Connections to the Themes

- 🤝 Sociedades en contacto / Societies in Contact: "Romance de la pérdida de Alhama" presents the characteristics of this theme in two ways. First, it portrays the Reconquista of Spain and the geographical context of its final stage. Furthermore, even though the plot of the romance has to do with the history of the Moors in Spain, the poetic voice is Christian. The bias of the Christian poetic voice can be found in the verse "cristianos de braveza," something that no Muslim in Al-Andalus would have said. In addition, the last scene between the alfaquí and the Moorish king would probably not happen in reality and only occurs in the romance to advance the agenda of the Christian author who sought to minimize Boabdil's legacy.

- ⚔️ El Imperialismo / Imperialism: This poem shows the effects of the Spanish Reconquista on the Moors, although from a skewed perspective. The Moors were devastated at the loss of their kingdom of Granada to the Christians, while the Christians were likely overjoyed that they had completed their Reconquista.

Literary Devices

- This romance is octosyllabic and has an assonant rhyme scheme in even verses (e.g.. “por la ciudad de Granada . . .“hasta la de Vivarrambla”).

- It includes a chorus (estribillo) — “¡Ay de mi Alhama!” — which highlights the devastating end of Al-Andalus, and the despair the Moors felt as the last kingdom fell to the Christians. 😔

- To preserve the number of syllables throughout the romance, the author uses sinalefa to reduce the number of syllables to in the verses that have more. The sinalefa combines vowel syllables into a single syllable when necessary. See the following examples:

- “y en un caballo cabalga” has 9 syllables (y/en/un/ca/ba/llo/ca/bal/ga). To protect the 8-syllable meter of the romance, sinalefa is used to combine the first two syllables in one (y-en/un/ca/ba/llo/ca/bal/ga)

- Sinalefa can also be used to combine two syllables even if the second begins with an h-. For example, the verse “juntado se ha gran batalla” includes 9 syllables (jun/ta/do/se/ha/gran/ba/ta/lla), but by combining syllables 4 and 5 (jun/ta/do/se-ha/gran/ba/ta/lla), the poetic voice maintains the eight-syllable meter.

- The author also uses hyperbaton (hipérbaton) several times to preserve the rhyme scheme of the poem. Hyperbaton changes the order of words within a verse so that it ends with the desired rhyming sound. For example, the author of the romance could have written “echó las cartas en el fuego / y matara al mensajero” in the second stanza, but given that the prior rhyming verse ended with an –a, the author shuffled words around so that the verse “y matara al mensajero” also ended with an –a , “y al mensajero matara”.

- This poem contains polifonía because it contains many different poetic voices, such as the narrator, the elderly Moor, and the alfaquí.

- Since many people in the Middle Ages couldn't read, this poem was recited orally, sometimes as a song. It demonstrates the oral tradition of Spain in this time period. 🗣

- The odd verses in the poem do not have a rhyme scheme, so this poem also contains blank verses (versos blancos).

Selected Quotes

“Que cristianos de braveza / ya nos han ganado Alhama” It is revealed in this verse that the poetic voice is Christian because a Muslim poetic voice would not have had a positive perspective faced on the Christian Reconquista.

“Mataste los Bencerrajes, / que eran la flor de Granada / cogiste los tornadizos / de Córdoba la nombrada.” The alfaquí highlights the bad decisions of the Moorish king and then concludes that the king deserves to lose his kingdom. 👑

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🏇Unit 1 – La época medieval

🛳Unit 2 – El siglo XVI

🖌Unit 3 – El siglo XVII

🎨Unit 4 – La literatura romántica, realista y naturalista

🤺Unit 5 – La Generación del 98 y el Modernismo

🎭Unit 6 – Teatro y poesía del siglo XX

🌎Unit 7 – El Boom latinoamericano

🗣Unit 8 – Escritores contemporáneos de Estados Unidos, y España

✏️Frequently Asked Questions

🙏Exam Reviews

© 2023 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.