What To Do When Friends Disclose Mental Health Problems to You

6 min read•september 24, 2021

fiveablejoon

fiveablejoon

Health & Wellness 😀

18 resourcesSee Units

We’ve all been there. A friend says “I want to tell you something – do you promise not to tell anyone?” And you automatically say “Of course.” Because you’re a good friend – and good friends listen, and keep confidences safe.

But then your friend tells you something that scares you. Maybe they have been considering self-harm or are thinking about suicide. Or, perhaps they are struggling with an eating disorder. Or experienced harassment. Or are abusing different substances.

These kinds of very personal disclosures from friends are tricky. On the one hand, we want to be a “safe place” for our friends. We are glad they are talking to us. We feel special, and close to them, to be the one they trust to confide in. On the other hand, we are worried about them and don’t feel equipped to handle this information. What do I say? What do I do?

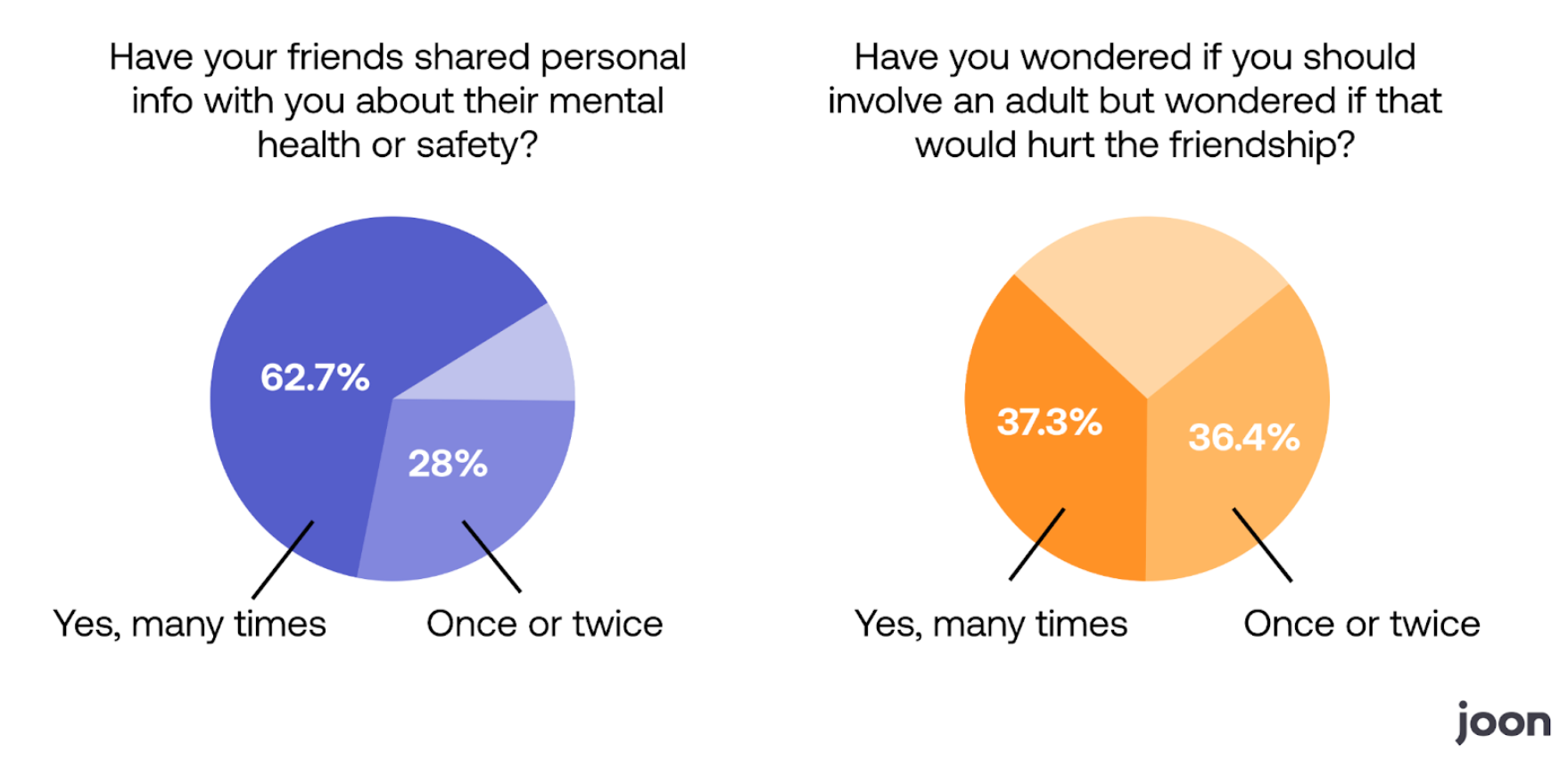

Our most recent Fiveable survey found that over 90% of teens reported that their friends had shared personal information about their mental health or safety to them. And more than 60% said that this disclosure led to significant worry about their friend and wondering when/if to involve an adult or otherwise get their friend some help.

In this blog we will answer a few common questions about what to do when friends disclose mental health problems to you:

How Can I Support a Friend in Need?

One of the first things to realize is that there is a big difference between being supportive and solving someone else’s problems. Often friends are disclosing personal information simply to seek some support, and don’t want or need help “solving” the problem. This helps a lot, because it is easy to be supportive. Support looks like:

- Listening. Simply listen. Let them describe what is going on. Ask clarifying questions such as “Tell me what’s going on” or “How are you feeling about it?”

- Validating. Validating means affirming that their emotions and experience are legitimate. This can be things such as “I understand why you feel this way”, “Wow, that sounds really hard”, and “Totally makes sense to me why you feel the way you do.”

- Support their own problem-solving. When the time feels right, ask them “What are you doing about this?” or “What kinds of options have you considered?”

Often the best way we support friends is to simply be a friend – and that means listening, validating, and supporting them as they try to navigate their difficult situation.

When and How Do I Break a Promise to Keep a Secret?

When your friend confides something in you that you suspect could mean they, or someone else, are in danger, it’s time to break that secret. Remember, your safety and the safety of others is more important than hurt feelings or breaking trust. Try this conversation opener if you don’t know where to start:

“Thank you for telling me this secret, I’m glad you trust me. This problem is too big for us to solve alone and we need help. Who is a safe adult we can tell?”

By partnering with your friend to agree on an adult to tell together, you may be helping them make a healthy choice they were scared to make alone.

If your friend is in an emergency situation – meaning they may not be safe right now, you may need to break that secret and tell an adult without their permission. While this is hard, remember, your duty as someone who loves them is to do your best to keep them safe. Secrets should be broken when they compromise safety.

Some examples of times when safety is more important than secrets are:

- If they you they are being hurt physically or sexually by an adult or a peer

- If they tell you they’re thinking about suicide and have a plan or have made an attempt

- If they tell you they’re thinking about hurting other people

- If they tell you they’re planning to run away from home

- If they tell you they’re planning to meet someone from online, and no one else will know where they are

What if the Adults in Our Lives Aren't Great Resources?

Ideally, you’d talk to your parent or your friend’s parent if there is a significant concern. Parents are most likely to be able to get your friend the help they need. But not all of us have parents who are supportive or who understand mental health concerns.

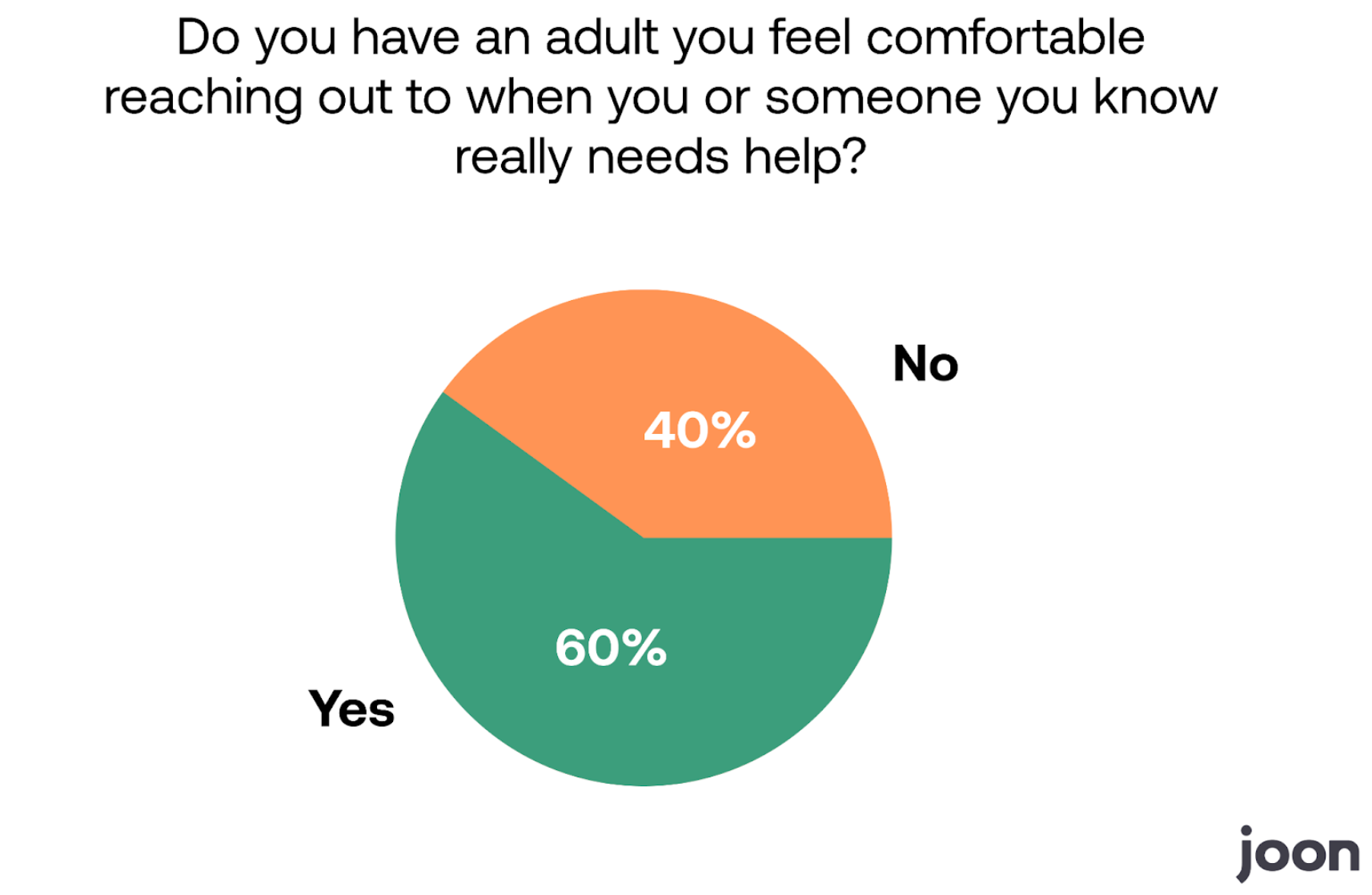

In fact, nearly 40% of teens reported they did not feel they could reach out to their parent for help. One even wrote in:

“Many of my friends’ parents and my own believe that mental illness is a synonym for ‘crazy people’ and that mental health care is a scam. They’d prevent my friends from getting help which would make it even worse.”

You might consider other safe adults in your life:

- a school counselor (they are often offering online appointments right now, too, just ask your teacher if you don’t know the counselor already)

- a teacher

- a coach

- another family member you trust

Crisis resources can also help get you and your friend through tough times. Visit the Joon resource page for crisis resources you can share with your friend. In many (not all) states teens are allowed to seek mental health treatment without parent consent. Cost remains a concern, of course, but school resources or community mental health clinics may have low-cost or no-cost support options.

How Do I Protect my own Mental Health While Being a Supportive Friend?

Here are a couple of signs that being your friend’s confidante could be creating a mental health burden for you:

- You are spending large part of your day worrying about your friend

- Worry about your friend is distracting from other tasks

- You’re losing sleep or your appetite because of worry about your friend

- You feel pressured to make time for them even when you’re not available

- You feel like the “only one” your friend has to rely on

- No amount of advice or listening improves your friend’s situation

What do you do when you realize that being your friend’s confidante has become harmful to you or them, but you don’t want to hurt or alienate them by setting a boundary? Here are a couple of conversation ideas that might help:

- Redirecting: “I’m so sorry you’re still struggling with your girlfriend. Let’s find something else distracting to talk about.”

- Validation: “I love being the person you talk to, and I want to keep being that person in the future, but this is weighing on me, so I need a break from this topic for a week or two.”

- Recruiting: “I know you’ve said I’m the only one you can talk to about this, but I really think [other person] is a good friend/family member, too. Can I help you tell them what you’ve been going through?”

- Direct: “I don’t want to hurt you, but this is too heavy for me right now, can we please talk about something else?”

Being a confidante comes with a lot of pressure and responsibility. Again, if you are in crisis, you can visit resources available on Joon’s teen crisis resources page.

Authors: Amy Mezulis, PhD and Katey Nicolai, PhD

- Amy Mezulis, PhD, is a licensed clinical psychologist who received her BA from Harvard University and her MA and PhD in Clinical Psychology from University of Wisconsin – Madison. Dr. Mezulis provides services to older children, adolescents and adults utilizing an evidence-based, cognitive-behavioral approach that includes mindfulness and acceptance-based treatments. Dr. Mezulis has specialized training in mood and anxiety disorders, eating disorders, suicidality and self-injury, trauma, substance use, and adolescent development. She is currently on the faculty at Seattle Pacific University, where she chairs the Clinical Psychology PhD program.

- Katey Nicolai, is a licensed clinical psychologist who received her PhD in Clinical Psychology from Seattle Pacific University. Dr. Nicolai provides services to adolescents and adults using evidence-based treatment rooted in cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic therapies, including Dialectical Behavior Therapy, interpersonal therapy, and family systems. Dr. Nicolai has specialized training in treating trauma and PTSD, personality disorders, self-harm and suicidailty, family problems, emotion dysregulation, and mood and anxiety disorders.

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🤝Community Service

© 2023 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.